Nearly 30 years after its release and a decade after it became the song of Euro 2016, it’s time to move on from Gala’s Eurodance anthem

In 1996, an Italian photography student named Gala Rizzatto recorded and released a dance song. Nearly three decades later, that song has become the single most inescapable sound in world soccer. It has been a meme. It has driven transfer policy. It has become the official song for the most corporate tournament in the sport’s history. It is time for someone to please free the soccer world from “Freed From Desire.”

Rizzatto, who performs mononymously as Gala, tapped into the cresting wave of industrial synth-driven dance pop hits that dominated ‘90s rave culture and with a propulsive four-on-the-floor singalong. “Freed From Desire” gradually became a chart sensation across Europe, one of the last hits from the Eurodance era and perhaps one of the most enduring.

As ‘90s European rave megahits go, “Freed” is genuinely pretty good, resisting the poorly-aged gimmicks that define many of the big songs from that time, from the offbeat talk-rapping of Eiffel 65 to whatever was going on with Scatman John. In the song’s biggest moments, Gala also eschewed hyper-digital synths that defined a genre obsessed with the Windows 95 aesthetic for a driving grand piano during the chorus and and earworm “na na na” post-chorus. The gesture towards real, rather than virtual instruments, creates a song that is a little more tactile and a little less frozen in 1997 amber.

“Freed From Desire” was a hit in its day, and remained an ever-present in European stadium playlists through the 2000. Its warpath to dominating terraces and PA systems did not truly begin, however, until 2016, when a fan of Wigan Athletic uploaded a YouTube video celebrating the recent form of his team’s Northern Irish striker Will Grigg.

It was a perfect match: “Will Grigg’s on Fire” scans neatly onto the chorus, there isn’t any particularly complex rhythm to navigate when you’re several pints deep, and half of the lyrics are “na na na” so even if you don’t quite get the words you can still join in.1An underrated thing about this whole phenomenon is that the first half of the video is an entirely different attempt at a “Will Grigg’s on Fire” chant set to to “Girl on Fire” by Alicia Keys, which presents a sort of weird alternate history where the first half of the video goes viral instead and Alicia Keys buys another house off of Europa Conference League Finals pre-match performances.

“Will Grigg’s on Fire” also had perfect timing: Grigg was a key member of a Northern Irish squad that had qualified for that summer’s European Championships, their first major international tournament since the 1980s. Eager for a party, Northern Ireland fans immediately adopted the chant, traveling in droves to France that June to serenade for their beloved League One star2Will Grigg did not score a goal or play a single minute at Euro 2016. with Eurodance.

The peak of the Will Grigg portion of the story came three years later. In season two of the Netflix documentary series Sunderland ‘Till I Die, it is heavily implied that the club’s new chairman — a business genius thought leader blowhard named Stewart Donald — was convinced to spend a League One record transfer fee on Grigg at least in part because he loved the song.

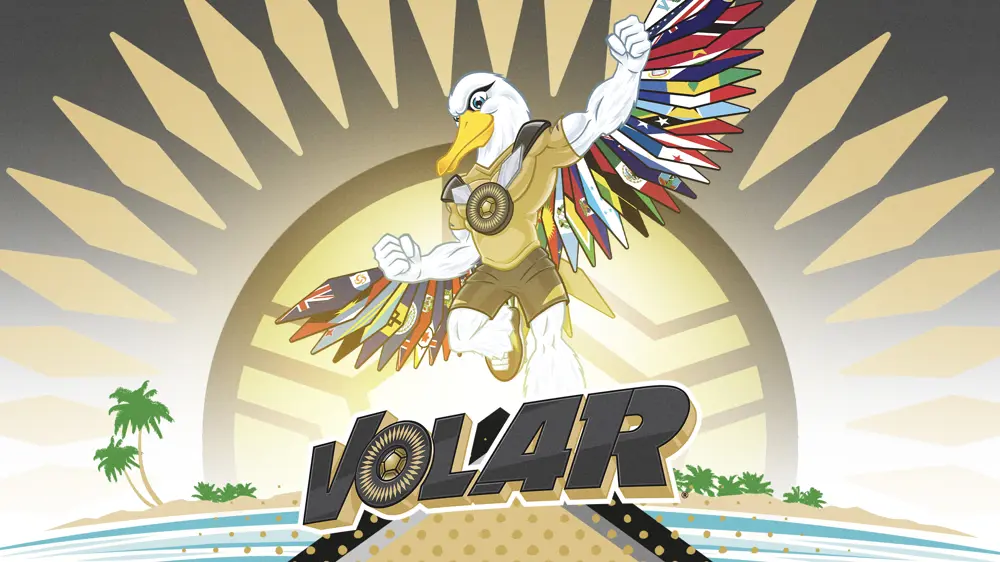

The beauty of soccer chants is how malleable and liftable they are, and in the decade since Will Grigg’s moment in the spotlight, “Freed From Desire” has been borrowed by supporter groups around the globe. Any striker in the world can be on fire, as long as you can get their name to fit in two syllables. The song became ubiquitous, played as the goal song for several teams at the 2022 and 2023 men’s and women’s World Cups and in the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2024 Olympics. It is, of course, the official song of the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup.

And now we must say enough.

This has been fun. The fact that it started with a random Wigan Fan and journeyman lower division striker is funny. The song is pretty good. Please, let us find a new song.

It has been 30 years since “Freed From Desire” was a hit, and even then it was a hit from a subgenre that was rapidly declining in popularity. While Eurodance died down at the turn of the century, they certainly did not stop making dance music in Europe — and lots of those songs feel like obvious heirs to Gala. “Mr. Saxobeat” is a little goofier but just as malleable, particularly if you sing the horn line. Stromae’s 2010s Eurodance revival masterpiece “Alors on danse” also presents fans with a horn line that can take the place of the post chorus singalong from “Freed For Desire,” and just three syllables to adapt and memorize. Noted book influencer and alleged Liverpool and/or Arsenal supporter Dua Lipa has an entire catalogue of songs that are dying to be repurposed.3“Houdini” has particular potential here, and Liverpool fans have already adopted “One Kiss,” although that song is yet to get the full Will Grigg lyrical treatment.

It doesn’t even need to be Eurodance. The sound of soccer has been defined by the magpie quality of its supporters: Over the course of the last century or so everything from Verdi operas to Detroit garage rock has become a staple of soccer stadium singalongs. “Freed From Desire” is an important part of that tapestry, but it has now fully crossed over from fun and organic to inescapable advertisement. It’s time for a new entry into the soccer music canon.